| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Condition Name | Extramammary Paget’s Disease (EMPD) |

| Disease Type | Intraepidermal adenocarcinoma |

| Commonly Affected Areas | Vulva, scrotum, perianal region, penis, axilla |

| Typical Age Range | 50 to 80 years |

| Gender Distribution | More common in females (especially vulvar), but also affects males |

| Associated Cancers | Bladder, prostate, cervical, anal, and rectal cancers |

| Diagnostic Method | Excisional biopsy with immunohistochemistry |

| Common Symptoms | Redness, scaling, itchiness, tenderness, slow-growing skin lesions |

| Primary vs. Secondary | Primary – arises in skin; Secondary – spreads from internal carcinoma |

| Reference Link | https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24266-extramammary-pagets-disease |

Extramammary Paget’s disease, which frequently mimics benign skin conditions but has far more serious consequences, has received renewed attention from experts in recent years. This uncommon form of skin cancer, which typically manifests as red, scaly, itchy patches, starts out subtly and gradually spreads to the skin and, in certain situations, internal organs. It affects areas such as the vulva, scrotum, perianal area, and penis. Many patients have usually tried rounds of antifungal creams, steroids, or antibiotics with little improvement by the time they are properly diagnosed.

The likelihood of developing EMPD rises by the age of 60, especially for postmenopausal women. This increase is not significant, but it is sufficient to cause dermatologists to become concerned. Many women believe that EMPD is just a recurrent yeast infection or chronic dermatitis because the vulva is affected in 65% of all cases. Because of this delay in precise identification, cancerous cells have more time to spread. These cells are frequently derived from skin appendages such as sweat glands, but in rare instances, they are connected to underlying cancers like prostate, bladder, or rectal cancer.

To put it in perspective, consider the gradual deterioration of the foundation caused by a minor leak in a house. That is the course of EMPD. It sneakily persists, slowly spreading, and ultimately necessitates much more intrusive care than if detected early. Some cases, astonishingly, don’t show any symptoms for years. Almost always, surgery is required by the time nodules or ulcerations show up.

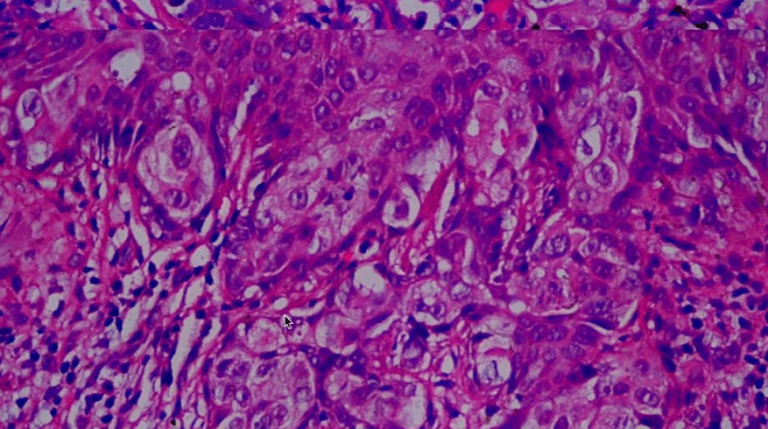

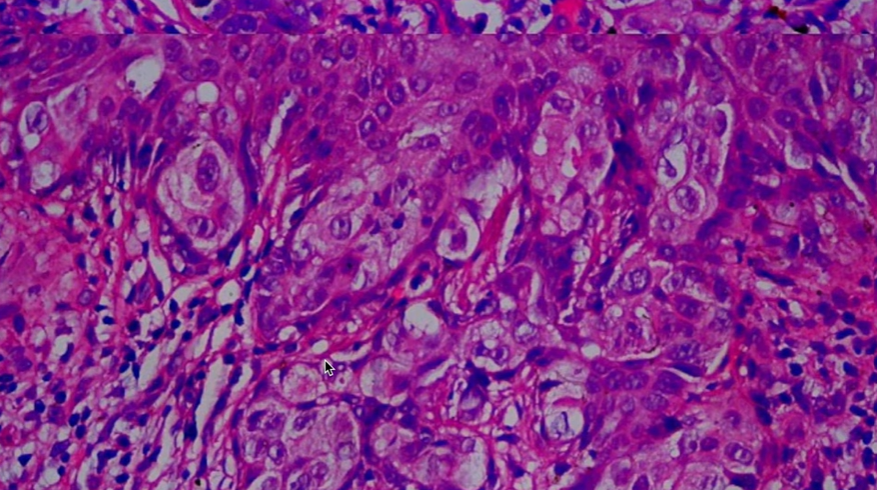

Accuracy is necessary for the diagnostic procedure. Immunohistochemical staining aids in the detection of particular cancer markers, such as CK7 or HER2, and is a better option than a routine skin biopsy. In addition to confirming the diagnosis, these markers might also direct new therapeutic approaches. Interestingly, targeted biological therapies that were previously used to treat breast cancer are now being investigated for EMPD because HER2 positivity in this rare disease opens the door.

Mohs micrographic surgery is now a very useful method, especially for superficial and well-contained lesions. By removing cancerous cells layer by layer, doctors can preserve healthy tissue and lower the chance of recurrence. Recurrence, however, is still a persistent worry. Even after being completely removed, EMPD has the annoying tendency to reappear up to 30% of the time. When surgery is not an option, radiation therapy—which is frequently considered a secondary treatment—proves to be very effective, particularly for elderly or immunocompromised patients.

The demographic trend is remarkable. Concerns regarding potential genetic or environmental factors have been raised by the notable prevalence of EMPD in older Asian men and older Caucasian women. Although there is currently no conclusive evidence of a single cause, associations with immune suppression, hormonal changes, and chronic inflammation are being investigated. According to certain reports, EMPD and HPV infections have co-occurred, making diagnosis and treatment even more challenging.

Rare dermatologic cancers, particularly those that coexist with internal cancers, have drawn more attention from medical researchers in the last ten years. This trend is supported by EMPD, which falls into the medical gray area between oncology and dermatology. Studies are now looking at how AI-based dermatoscopic tools can spot subtle patterns in EMPD that might be difficult for humans to notice thanks to strategic partnerships between hospitals and academic institutions. Clinicians hope to drastically cut down on diagnostic delays, which typically last 18 to 24 months, by utilizing AI.

Because celebrities like Selena Gomez and Kim Kardashian have been vocal about psoriasis and lupus, skin health has become more well-known in pop culture and celebrity circles. Even though EMPD hasn’t gained widespread recognition, advocacy potential still exists. Public awareness would skyrocket if just one well-known patient shared their story. This is similar to how conversations about head and neck cancers were triggered by Michael Douglas’ revelation about tongue cancer, another disease that is frequently disregarded.

From the perspective of public health, EMPD highlights a more profound systemic issue: social stigma surrounds many skin conditions, especially those that affect intimate areas. For fear of embarrassment or discomfort, patients frequently avoid talking about their symptoms, which lets the illness worsen. Healthcare providers need to create environments where these issues are discussed early, sympathetically, and without presumption. Programs for community outreach, particularly with older populations, have the potential to be transformative.

Clinically, EMPD and its mammary counterpart, Paget’s disease of the breast, have been compared. Although they have different origins, they share similar histologic characteristics. The attempt to categorize EMPD based on genetic profile as well as geography is especially novel. In the upcoming years, treatment protocols may be significantly changed by this shift toward personalized dermatologic oncology. HER2-targeted medication trials are already under way, giving patients with recurrent or metastatic disease fresh hope.

The everyday reality for patients with EMPD may include scarring, difficulty navigating sexual relationships, or fear of recurrence. Although online forums have given people a place to share their experiences, there are still few support groups. Stories of resiliency, like getting back to your regular life after treatment or getting remission after several surgeries, are shared in these settings with remarkable clarity and support.